March 22, 2025, 2:36 pm | Read time: 5 minutes

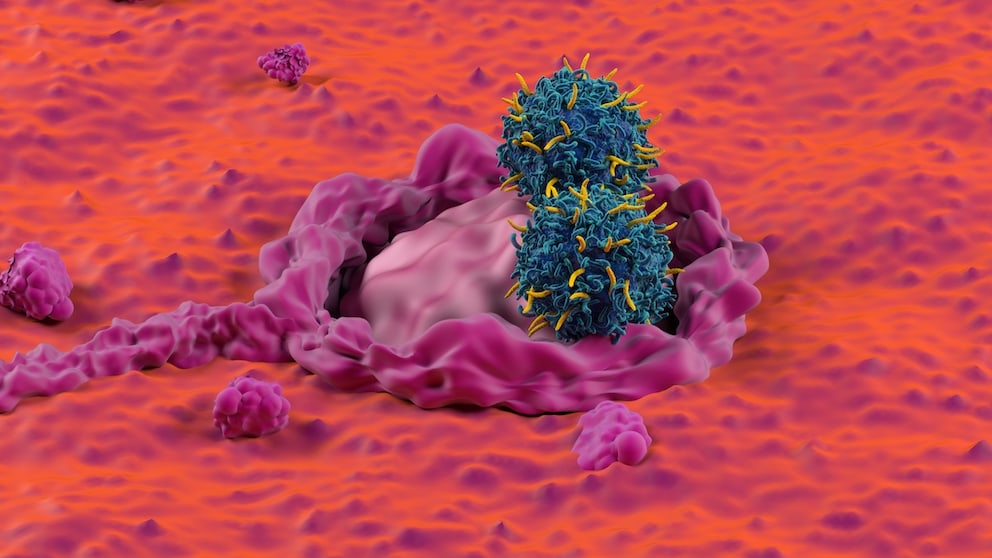

Immunotherapies are seen as a beacon of hope for certain forms of cancer — but how effective are they in the real-life treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer? A new US study provides answers based on data from almost 19,000 patients.

In Germany, colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer in women and the third most common cancer in men.1 Worldwide, around 1.4 million people are diagnosed with colorectal cancer every year, and around 700,000 die from it.2 The earlier the disease is detected, the higher the chances of survival. A group of researchers at the Cleveland Clinic in the USA has now found yet another treatment option that can significantly increase the chance of surviving colorectal cancer.

Overview

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors as a Possible Treatment for Colorectal Cancer

In 25 percent of colorectal cancer patients, metastases, i.e., malignant cancer metastases, are already present at the time of diagnosis. In a further 25 percent, metastasis occurs later in the course of the disease.3 In principle, a distinction is made between microsatellite-unstable metastatic colorectal cancer (MSI) and microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer (MSS). For the sake of simplicity and better understanding, we will always refer to unstable or stable tumors in the following.

In general, microsatellites refer to a specific DNA segment in the tumors that can be either stable or unstable. The unstable form is based on a DNA repair defect that causes the DNA section to be shorter or longer than normal tissue.4 Patients with the unstable form, in particular, do not respond to conventional treatments, which is why the researchers in this study took a closer look at the extent to which immunotherapy with so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors makes sense. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are special antibodies that are designed to reactivate the immune system. They do this by preventing cancer-related blockages through the activation of an immune checkpoint. In stable tumors, however, there is no such change in the DNA segments, which is why treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors has been avoided in the past, as it might not respond.

The present study, therefore, had three objectives: Firstly, the researchers wanted to identify factors associated with the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.5 Secondly, they wanted to understand the relationship between immunotherapy and survival in more detail. The third aim was to identify possible subgroups that responded well to immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly patients with a stable form of colorectal cancer.

Data Analysis of Almost 19,000 Patients

The retrospective cohort study was based on electronic health records from the Flatiron Health database. A total of 18,932 adult patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who had at least two documented clinic visits between January 2013 and June 2019 were included. Follow-up was conducted until the end of 2019.

In addition to sociodemographic data, cancer-specific information, such as tumor characteristics, disease stage, and tumor mutation status, was examined at the time of initial diagnosis. In addition, patient records were searched for information on treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors and date of death. The following drugs were considered to be immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy:

- Nivolumab

- Pembrolizumab

- Atezolizumab

- Ipilimumab

- Tremelimumab

- Durvalumab

- Avelumab

Higher Chance of Surviving Colorectal Cancer with Immunotherapy

Of 18,932 patients, 566 received immunotherapy during the course of their treatment. This was used significantly more frequently in patients with an unstable tumor and metachronous metastasis (metastases that occur 92 days after the initial diagnosis). Patients with the former form of cancer who received immune checkpoint inhibitors as treatment had a 63 percent higher chance of surviving colorectal cancer than patients who received chemotherapy alone. The duration of therapy was significantly longer for unstable tumors.

Another interesting finding: among the 235 patients with an unstable tumor who received immune checkpoint inhibitors, 12.3 percent showed a sustained treatment response, i.e., a treatment duration that lasted longer than six months. High albumin levels in the blood — one of the most important binding and transport proteins — and simultaneous administration of antibiotics were associated with better survival rates and a longer duration of therapy in patients with both stable and unstable colorectal cancer. In tumor patients with the stable variant, women and patients in good general health, in particular, benefited from immunotherapy.

Good Therapy Option

The study confirms that immune checkpoint inhibitors are also an effective initial therapy for patients with unstable tumors in everyday practice. Their effect in this patient group is superior to purely chemotherapeutic approaches in terms of both survival and duration of treatment. However, it is also noteworthy that a small but relevant subgroup of patients with stable tumors — previously classified as unresponsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors — benefited from the treatment. The positive associations between antibiotic administration, high albumin levels, and treatment response could indicate an immunomodulatory influence of the microbiome. The study thus opens up new perspectives for personalized immunotherapy approaches and underlines the relevance of individual biomarkers in the choice of therapy.

Study shows A severe coronavirus infection can possibly shrink cancer tumors

Researchers Alarmed! More and More Cases of Stomach Cancer in People Under 50

Malignant Melanomas Study Reveals Unexpected Factor for the Survival Rate of Skin Cancer

Study Classification

The study is impressive due to its large number of cases and practical relevance. In particular, the cohort with stable tumors that received immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy made it possible to draw well-founded conclusions about this previously little-studied patient group.

Nevertheless, there are limitations: Data on tumor mutation burden, genetics or concomitant surgery were lacking. Possible side effects of immunotherapy could not be systematically recorded either. In addition, the evaluation cannot establish any causal relationships. Conflicts of interest due to the use of a commercial database (Flatiron Health) are possible, but the company was not involved in the analysis.