March 16, 2025, 2:18 pm | Read time: 6 minutes

Vaccinations are important for a variety of reasons. Years ago, infectious diseases such as diphtheria, whooping cough, and polio were still life-threatening for children in this country. Thanks to vaccination, these diseases have been contained, if not almost eradicated. However, despite the WHO’s recommendation, not all children — even outside Germany — have been sufficiently vaccinated.

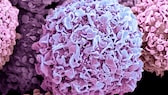

Infectious diseases such as diphtheria, whooping cough, mumps, and measles are highly contagious and can spread quickly. An illness can be life-threatening, especially in children. This is why the European vaccination information portal advises children to be vaccinated against these and five other infectious diseases.1 Measles, in particular, is extremely contagious and requires a vaccination rate of 95% to achieve herd immunity — a higher threshold than for many other vaccinations. Despite these recommendations, global vaccination coverage has stagnated for years and worsened further during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, more and more measles cases are now being counted worldwide.

Overview

- Measles Remains One of the Most Common Deadly but Preventable Childhood Diseases Worldwide

- Researchers Investigated the Question: How Many Children Missed Their First Measles Vaccination?

- Analysis of Measles Vaccination Coverage for Children

- Analysis Shows: More Than 20 Million Children Don’t Have Sufficient Measles Vaccination

- What Does This Large Vaccination Gap Mean?

- Classification of the Study

- Sources

Measles Remains One of the Most Common Deadly but Preventable Childhood Diseases Worldwide

“In 2019, an estimated 1.5 million children under the age of five died worldwide from vaccine-preventable diseases. Measles remains one of the leading causes of death in children from vaccine-preventable diseases,” reads the introduction to a recent study in which researchers investigated the global vaccination coverage rate for measles and DTP, the triple vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough.

Epidemiologist Stephanie Vaccher and other scientists were also interested in a possible connection between the two vaccinations. They also wanted to find out whether children who had missed the DTP vaccination had also not received a measles vaccination.

Researchers Investigated the Question: How Many Children Missed Their First Measles Vaccination?

They also examined whether the current definitions of “under-immunized” children truly encompass all children at risk. A child is considered “under-immunized” if they have not received all three DTP doses. (The term “zero-dose child” refers to children who have missed the first DTP vaccination ). A skipped measles vaccination, on the other hand, is not included in the term — a general problem from the researchers’ point of view, as measles is highly contagious, and its vaccination gap could be an equally critical indicator for healthcare.

The researchers, therefore, asked themselves the following questions: How many children worldwide missed their first measles vaccination in 2019 and 2022? How does this group differ from children who have not received a DTP vaccination? And which countries are particularly affected? The study was published in the journal Vaccines.2 FITBOOK took a closer look at the results.

Analysis of Measles Vaccination Coverage for Children

The researchers used publicly available data from the WHO/UNICEF National Immunization Coverage Estimates (WUENIC) for 2019 and 2022. Vaccination rates for the first and third DTP vaccinations and the first measles vaccination were analyzed and combined with the population figures for children under two years of age from the UN population estimates.

The analysis also took into account the socio-economic situation of the countries based on the World Bank classification (low, lower, upper-middle, and highly developed countries). Standard statistical methods were used to investigate the discrepancy between the vaccination rates. In addition, the so-called “dropout” was calculated – i.e., the difference between children who received a vaccination and those who did not receive a further dose.

Analysis Shows: More Than 20 Million Children Don’t Have Sufficient Measles Vaccination

The researchers’ analysis reveals a worrying trend. According to the analysis, an estimated 14 million children worldwide had not received the first DTP vaccination (DTP1) by 2022. The number for measles vaccination is even higher: The report indicates that 21 million children did not receive their first measles vaccination. 96 percent of these “under-immunized” children lived in low- or middle-income countries.

Comparing vaccination coverage in 2022 with 2019, the researchers discovered:

- In 2022, DTP1 vaccination coverage was 95 percent, while measles vaccination coverage was only 90 percent. In low-income countries, the latter even fell to 83% compared to 2019.

- The difference between the first DTP and the first measles vaccination is particularly large in poorer countries. While only two percent fewer children in high-income countries received the measles vaccination than the first DTP vaccination in 2022, the difference in lower-income countries was six percentage points.

- Some countries with the highest numbers of unvaccinated children — such as India, Nigeria, and Pakistan — are heavily affected in all categories. Other countries, such as Montenegro, have very low measles vaccination rates but do not appear among the countries with the worst DTP coverage.

These results show that the current definition of “under-immunized” children overlooks many children who are specifically underserved for measles vaccinations.

What Does This Large Vaccination Gap Mean?

The high infectivity of measles and the large vaccination gap make it necessary to consider measles vaccination as a separate criterion for under-immunization. The study shows that children who receive DTP vaccinations are not necessarily protected against measles — and vice versa. This means that the current definition of “under-immunized” children has gaps, as it only focuses on DTP and ignores children at risk of measles.

This is particularly problematic for countries with unstable health systems: Defining children as under-immunized based only on their DTP vaccination may underestimate the risk of measles outbreaks. These, in turn, can not only cost children’s lives but also overburden entire healthcare systems.

Measles is also a disease that has particularly serious consequences in poorer countries. In addition to acute complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis, there are long-term effects such as subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). SSPE is an inflammatory, neurodegenerative disease of the brain and a fatal late consequence of measles infections.

Classification of the Study

The study’s results are derived from population data of individual countries, precluding any direct comparisons between individuals. In addition, there is a lack of regional and demographic data within the countries that would enable more detailed analyses.

Nevertheless, the study provides valuable insights into the gaps in global vaccination programs. The proposed addition of measles vaccination to the definition of “under-immunized” children could help to better target vaccination strategies to regions at particularly high risk of measles outbreaks.

Ensuring access to vaccinations remains a key challenge. The study highlights that measures such as the transition from 10-dose to 5-dose vaccine vials or the development of microneedle patches for measles vaccines could help to reach more children.

Study shows By 2050, 39 million deaths are expected to be attributable to antibiotic resistance

Researchers Identify One Factor Apparently Leads to More Heart Disease Than Smoking

Forecast Annual Breast Cancer Deaths Are Expected to Rise by 68 Percent by 2050

Conclusion

The analysis shows that children who miss measles vaccinations are not necessarily the same as children who miss DTP vaccinations. Relying only on DTP vaccination rates could, therefore, overlook many children at risk.

To better prevent measles outbreaks and improve global immunization coverage, the first measles vaccination should be included in global reports as an indicator of under-immunization. Only then can targeted vaccination programs be developed to reach the most vulnerable children.